Safe Way to Get Mental Health Help May Have Consequences Beyond Covid-19

May 15, 2020

Teletherapy, the new normal during the pandemic lockdown, is the only option for some in the United Kingdom and United States. People can get help for anxiety and other mental health problems without leaving their homes.

But for some people dealing with circumstances never seen or dealt with before, not having in-person therapy is a loss teletherapy cannot replace. The result could be long term consequences for college students no longer getting therapy, as well as others who are finding teletherapy, which can take place over the telephone or computer.

“It’s really, really important that when all of this is over and life seemingly goes back to normal, that we consider the fact that people’s mental health might not have gone back to normal yet and we don’t know what normal will look like or if the normal we knew will ever come back, “Marwah El-Murad, project manager at the Higher Education Mental Health Foundation in London, said.

In the U.K., mental health services are free through the National Health Service, but it can be difficult to obtain.

“Mental health services are at the bottom of the pile of the health service so it’s everything else that gets placed important and then mental health,” Emily Thomas, a college student from Lancashire, England said.

“Even though it’s becoming more acceptable, it’s still completely at the bottom,” Thomas, said.

Thomas, who attends college in Leeds, England, said her school only allows four counseling sessions maximum each year. After trying to get help from a private practice and being unsuccessful, Thomas thinks seeking help during Covid-19, “would be a lot more difficult” due to lack of resources.

“Lots of people aren’t able to access the regular program of support that they would normally access,” El- Murad said.

Mental health services that have been impacted by coronavirus, include group sessions, support groups and online counseling.

El-Murad also said that fewer college students have been seeking services.

“What that means is if [students] are experiencing any mental health problems, they are actually far less likely to talk about it to their peers or to seek support for that mental health problem, so there is still a long way to go.”

In the U.S., Michael Russo, director of Counseling and Student Development at Central Connecticut State University, also reported a decrease in students seeking help.

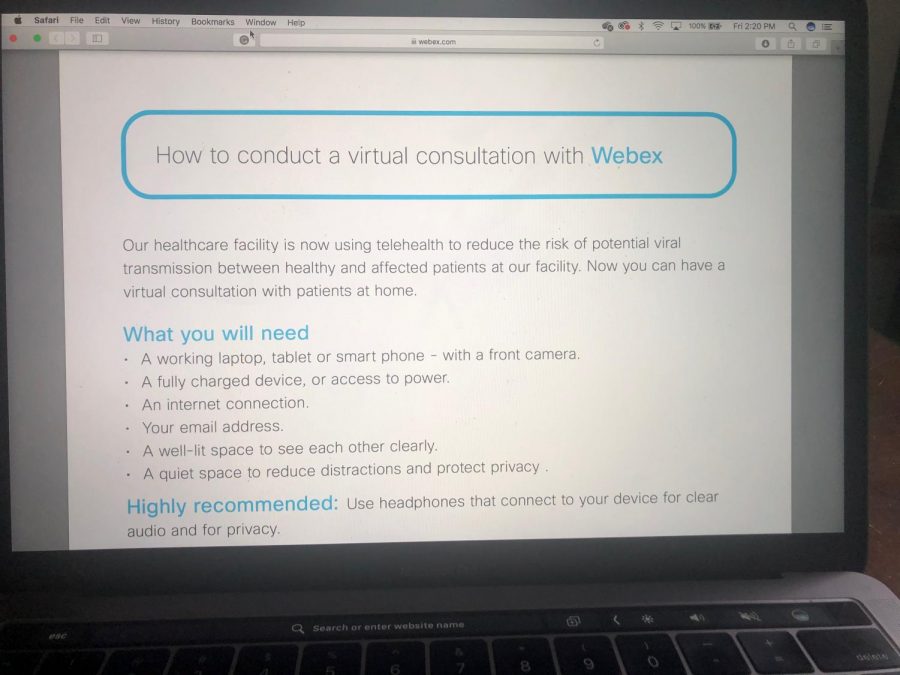

The demand for campus mental health services has risen across the country, with some authorities speaking of a college mental health crisis; Central Connecticut has witnessed that trend. Since the start of the fall semester, counselors at Central Connecticut saw a dramatic increase in the number of students seeking mental health services and that growth continued into the spring, according to Russo. After campus closed, the counselors got teletherapy up and running using WebEx in just 10 days, and expected to see a spike in students needing services.

However, after reaching out to all current or recent students who were utilizing services, about only 55 to 60 percent of students agreed to continue with teletherapy, meaning around 40 percent did not want virtual help.

Russo believes the drop in appointments may be due to students having less time due to the change in academics, family commitments or the lack of privacy of having to speak openly in a home rather than a private session.

“[COVID-19] has caused a mental health crisis and its impact will be seen long after the virus has passed,” Russo said.

Russo said that he, as well as the other CCSU counselors, are expecting to see the number of students utilizing services rise again once people are allowed back on campus.

Some young people with their own private therapists have found teletherapy lacking as well.

“I kind of felt stuck almost. Instead of taking steps forward I was taking steps back because I wasn’t expressing how I felt or things I was going through or am going through so [teletherapy] wasn’t that great,” 18-year-old Marina Dauti said about losing privacy during sessions in her home.

Dauti, who seeks services in Litchfield, Connecticut, recently resumed in-person therapy again after four weeks of teletherapy. Her therapist was still doing limited in-person sessions, however, she had to switch to teletherapy due to her father’s medical condition which she said was the only safe way to get services at the time.

Switching back to regular sessions for Dauti was a “relief.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KSIr2aD6ZWs

The rejection of teletherapy seems to cross across gender, ages, and social position.

Gregory Stackhouse, 34, a factory worker in Agawam, Massachusetts, was trying to seek in-person therapy but was frustrated when he found out that would not be an option.

Before the pandemic, the factory where Stackhouse works, which makes plastic display cases and other items, was not designated an “essential” business, but it has transformed into one as they are now making plastic sneeze guards for stores. Stackhouse said the work environment was becoming “more relaxed due to social distancing.”

Despite a more relaxed environment, Stackhouse said in an interview that he was seeking mental health services for the first time since childhood, and just wanted someone to talk to about his anxiety and panic attacks that he has been struggling with for some time. He also feels that he may have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to family issues over the last 10 years.

Privacy for Stackhouse isn’t a problem because he lives alone, but losing closeness by talking to someone through a screen is. However, after being told he could not get in-person sessions, Stackhouse said teletherapy is his only option.

After filling out an online application and doing an interview-like process over the phone, Stackhouse said he felt discouraged because of some of the questions he was asked, such as if he lived with anyone and if he would be able to pay for the service.

Although the people over the phone never expressed rudeness, Stackhouse said more in-depth questions made him feel that his situation may not be as serious as others in the counselors’ eyes.

Stackhouse said he had his first virtual appointment with his regular doctor because of constant migraines and felt a level of discomfort by not having him in the room while addressing certain questions.

After answering no to questions, such as “do you have numbness in the hands, tingling in the feet and coronavirus symptoms like lack of taste and smell, heavy breathing and tightness in the chest?” Stackhouse said his doctor said, “okay good, that means you aren’t having a stroke.”

“I don’t know if the emotion was conveyed by the look on my face when he asked that because he was looking at his computer from the side while I was talking to him so we were never face to face,” he stated.

Stackhouse worried that the level of discomfort he felt with his regular doctor may also happen if he uses teletherapy.

Despite this view about teletherapy, clinical social worker Briggitte P. Brown of Spirit Soul and Body Clinical Services, thought she would see a decrease in appointments but instead her caseload stayed consistent. She found that a lot of teenagers liked teletherapy, while older adults said they would wait to resume sessions when quarantine was over.

Brown works with a lot of clients who have experienced or are currently experiencing trauma and does a form of psychotherapy known as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR).

“I find that it’s been very, very difficult for those clients because of the lack of physical connection,” Brown stated. “We’re not seeing each other face-to-face and that’s been a really big struggle but those clients are becoming more independent because they don’t have a choice otherwise.”

Faster appointments than before are available at Central Connecticut, however, losing an in-person connection can be problematic for some high-risk patients.

“My biggest concern is student’s safety because as wonderful as our counseling staff is, I do get very concerned about students who may be thinking about suicide and making sure we are on top of that and focused on that and how we are meeting their needs,” Russo said.

Whether high risk or not, all levels of people’s mental health are different, especially if teletherapy may not be the solution for everyone needing help.

“It [teletherapy] doesn’t give me much confidence in resolving or addressing my issues,” Stackhouse said about losing closeness.

Angela Fortuna From Central Connecticut State University also contributed interviews for this report.