Recovering Hartford’s Hidden Past: Naming The Unnamed

November 25, 2019

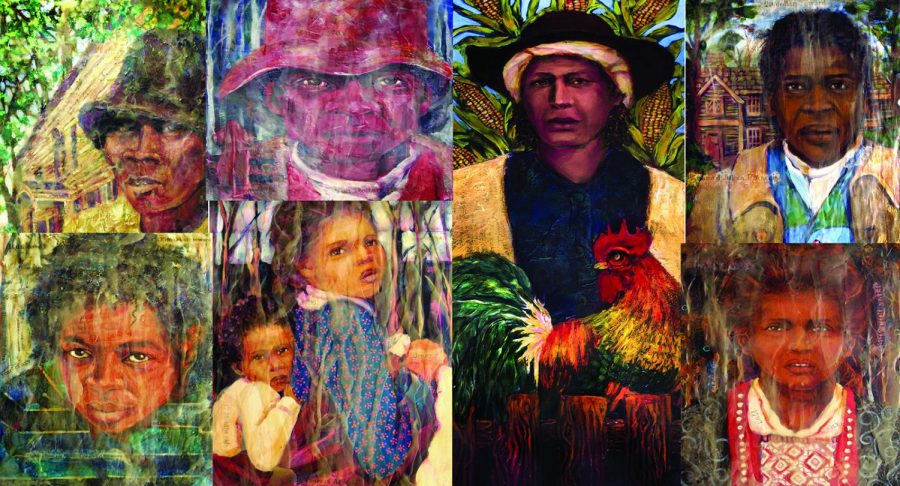

During the 17th and 18th century, around 6,000 individuals were buried in Hartford’s oldest cemetery the Ancient Burying Ground. Most of the minorities, who were Native Americans, Africans and African Americans, remained nameless with no headstone, proof or memory of their lives, until the Board of Directors identified the research gap and put a project together.

Today, some of these identities continue to remain unnamed but the list still are actively being built upon.

Central Connecticut history professor Katherine Hermes picked up the reigns of the project with her team of educators and alumni. They decided to create an in-depth scholarly research project known as “Uncovering Their History,” in which they dug up colonial Hartford’s least visible population.

“What we can say for certain is that Native and African men and women were among Hartford’s founding generations,” Hermes stated. “They lived and died here from its earliest days, fought in wars like the Pequot war, King Philip’s War, the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. They were not rare inhabitants, nor marginal to the town’s development,” she continued.

During her lecture, Hermes presented their extensive research in front of students, faculty and staff.

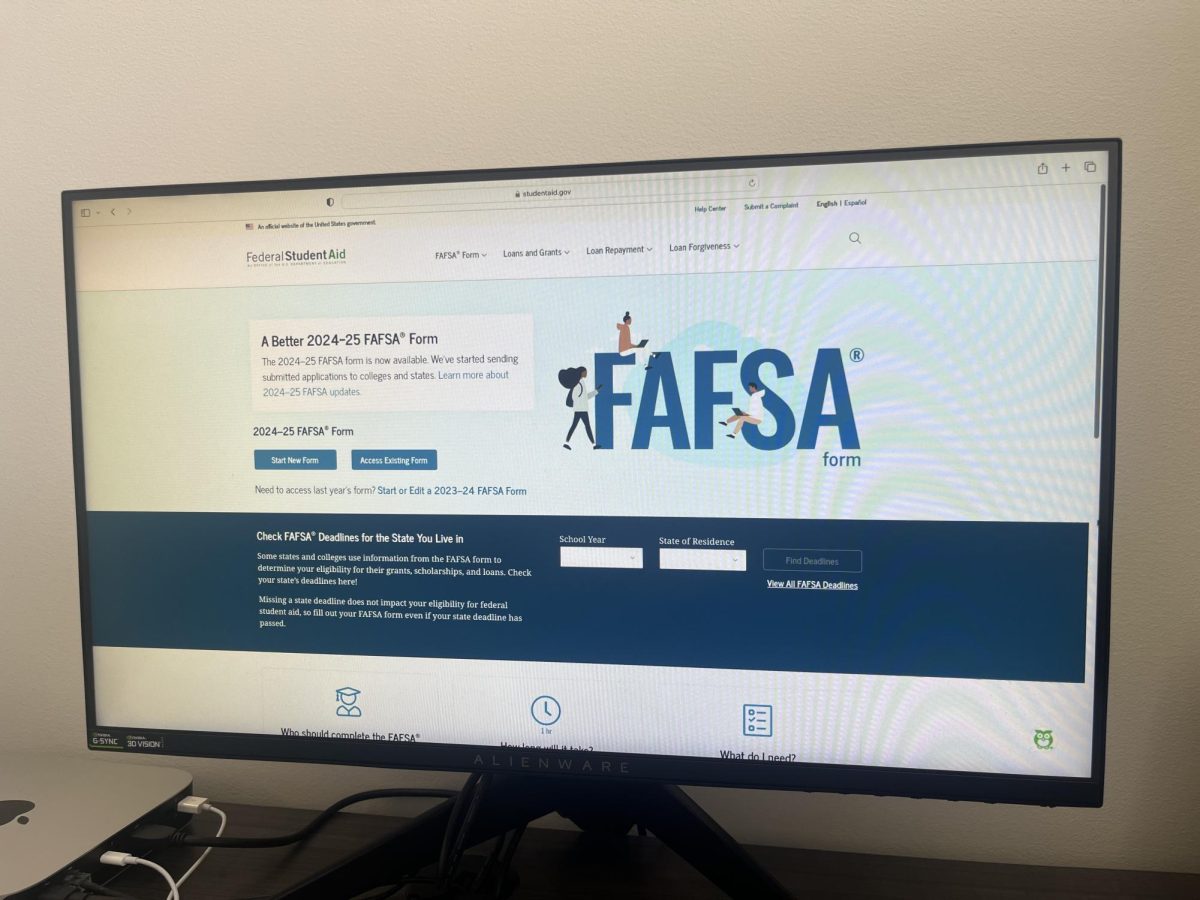

Part of her presentation incorporated their website they created, which has a list of over 500 people whose identities were lost but were able to be tracked down with access their personal information as well as their family and relationship tree. It also contains a downloadable database, the sources and narratives about various individuals and themes.

Along with this, Hermes shared the backgrounds of some of the newly identified diseased. These stories that had more “maybes” and “probabilities” than other histories of white colonists, because the sources used to gather details about them “can offer an obscure information about people of color,” as Hermes explained.

In fact, it was found in the research that this relates to nearly 125 unnamed people of color whose burials were recorded. Over the centuries, Sexton’s and others recorded the death dates, causes of death and sometimes ages and gender of people, while omitting their names. However, the master’s name was rarely missing.

“Few things mean more to us than our names. Our names connect us to ancestors, to places, to our accomplishments. We go to great lengths to protect our reputations, our good names,” Hermes added. “How could one be remembered if one had no name?”

She explained that even though the records for each person are numbered on the website, they deliberately decided not to use numbers to identify the unnamed to keep from dehumanizing them anymore.

“The dehumanization embedded in the institution of slavery is nowhere more manifest than in the denial of the ordinary dignities afforded to most people: a name of one’s own, the right to a family, to believe as one chooses, to organize one’s own time, to be remembered in death,” Hermes noted.

Hermes explained there are a number of reasons behind why the names were ignored.

First, the Natives and Africans were not historically important because they had no relationship with the government and were considered too uncivilized to be able to rule. Second, in the 19th century after the Civil War, the local historians of Hartford tried to minimize Hartford’s role with the institution of slavery and left enslaved people off of the published Sexton’s lists and the history books.

“In an us versus them mentality, the North was not the one responsible for slavery,” Hermes explained. According to her, evidence of enslavement got buried or downplayed which then helped in the rise of the reputation of abolitionist Connecticut.

Lastly, while there are plenty institutions that preserve papers from the history of wealthy white men in government, there is no single repository or identifiable boxes of papers that speak on people of color. Hermes believes that despite their lack of attention in the past, with more research, some of these individuals might finally be honored and named.

“Let’s make sure Hartford’s next generation learns a more complete story about its people and its struggles for freedom and equality,” Hermes stated. “These are the ones to whom we owe the most,” Hermes stated. “We owe them a truthful story.”

For more information, access the website africannativeburialsct.org.