With the prospect of terrorism hovering over our heads, things certainly have not changed since the Cold War era; fear always prevails in times of war. For this reason, Stanley Kubrick’s dark comic classic Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is as fresh as ever. Released in the middle of the Cold War in 1964, Strangelove is a biting commentary on the inept minds that run the military struggles in our world and how often our pitfalls come not from outside the good ol’ U.S. of A, but often from within. Funny, ain’t it?

Strangelove is the story of grave faux pas: a crazed general (Jack D. Ripper, played by stone-toned Sterling Hayden) who, out of delusion and paranoia, orders a unit of bombers to attack the Russian front. Despite the scrambling efforts of political and military minds alike, the orders are carried out and the Reds are nuked, causing a retaliatory chain of…well, I won’t reveal too much, but let’s just say it rhymes with booclear polocaust.

Despite the grim material, Strangelove is not a dreadful film. It should not inspire fear, but rather a clean escape from the tribulations of the current day. It is not a film that makes you feel any better about whatever state of battle we are in at the time, but in the case of the almost too true to life characters, sometimes it’s best to laugh at them instead of with them.

As if the story itself did not have a certain self-awareness, Strangelove is scored by acute irony. The soothing sounds of the opening credits are followed by a recurring revamp of “The Ants Go Marching One by One” (which no doubt is a jab at the immaturity of war in general, masked in sophistication). The famous final scene (a montage of nuclear explosions) is set to “We’ll Meet Again,” as the world meets its end via nuclear holocaust. Nihilistic cynicism or faith in a heavenly outcome, take your pick.

Though Stanley Kubrick is remembered for his dreamlike imagery in films like 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Shining, the style of Strangelove is more rigid in its black-and-white grittiness. It’s his last non-color film, but that is not to say that the film stock adds nothing; it matches the material suitably. Beginning with a voiceover about the rumored ‘Doomsday device’ from the Russians (a very real concept that thankfully was never executed), as well as title credits over stock footage of airborne bomber planes, Strangelove plays like one long propaganda film. This time instead of the attack coming from ‘them,’ it comes from us.

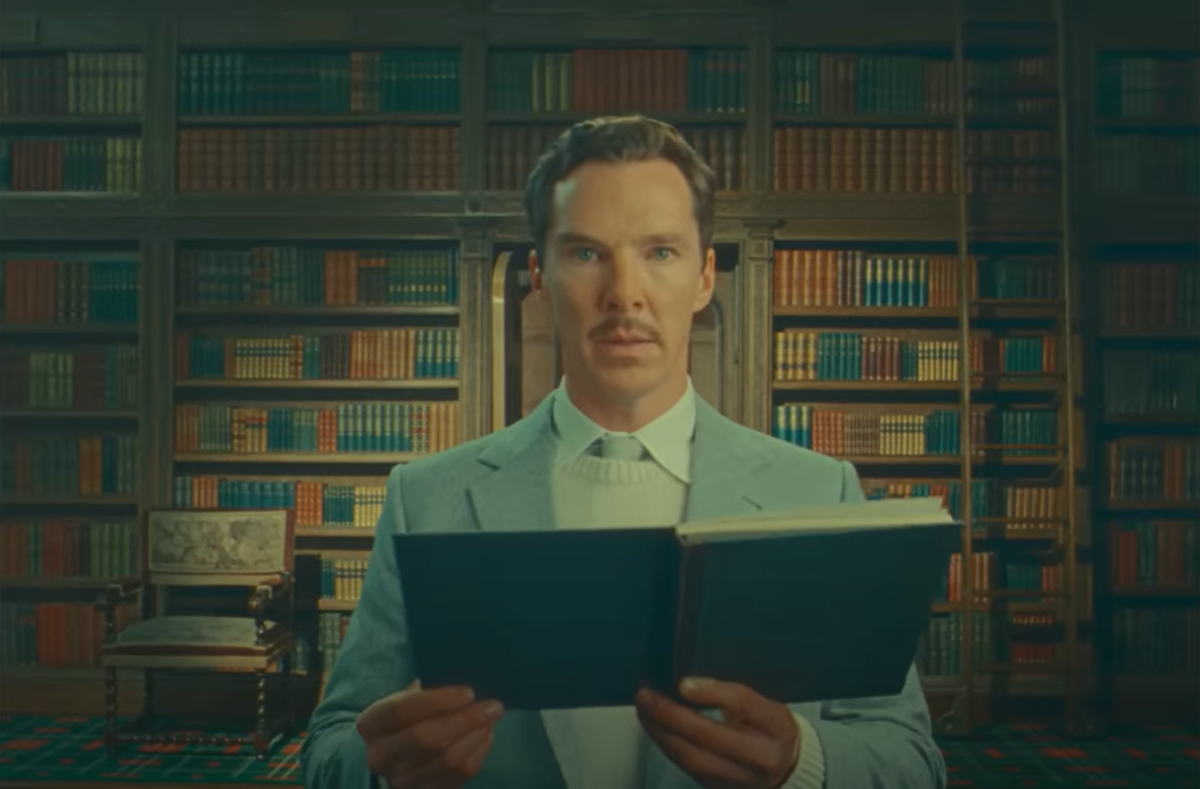

If there’s any single reason to watch Dr. Strangelove, it’s the great Peter Sellers, and if there’s any doubt of his acting credibility, this film will invert such doubt. Sellers slips right into each of his three roles, and in each case, he ceases to become recognizable. His portrayals of Mandrake, Muffley and Strangelove are golden in their own right, and they range from minimalist to outrageous. Though he received an Academy Award nomination for the three roles collectively, each one could have been individually recognized. Though it’s difficult to pick one scene as Sellers’ best, the most hilarious one to watch out for features him reporting the news of an impending nuclear attack to premier of Russia.

Sterling Hayden defines subdued yet cathartic paranoia in his portrayal of General Jack Ripper. He is cool, collected and insane. He brandishes his cigar like a salty cartoon character. An anti-Marxist Groucho Marx, you might say. In between puffs from his cigar, he offers Mandrake his two cents on the “impending” communist infiltration: “I will not sit back and allow…the communist conspiracy to sap and purify all of our precious bodily fluids.” We find out later that he discovered this theory during a bout of sexual inadequacy. Simple mistake which any person could have made.

The key to the Strangelove‘s success is its serious tone; not a single character has the slightest idea of the absurdity of what is going on. There is no poking fun at any of the characters’ names (Major “King Kong, Buck Turgidson), nor is there any intended irony in George C. Scott’s mannerisms. As Roger Ebert said in his essay on Strangelove, “A man wearing a funny hat is not funny. But a man who doesn’t know he’s wearing a funny hat … ah, now you’ve got something.” According to film lore, the tone was almost completely ruined before final cut. Kubrick filmed a giant pie fight as the finale, which is one alternate ending that is better left to pieces. The overall effect would have been lost, and while I am curious to see the alternate ending, I won’t be holding my breath for its recovery. Take my advice: appreciate the good things in life for what they are, especially if it’s Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.